Our Story

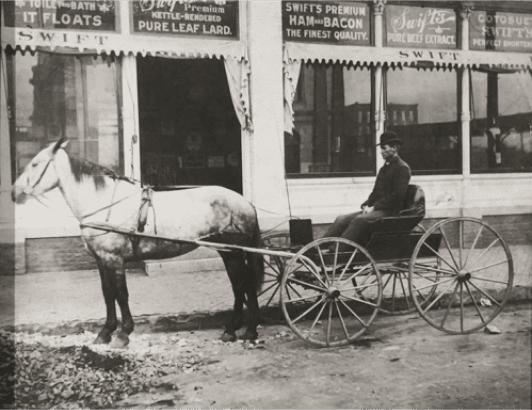

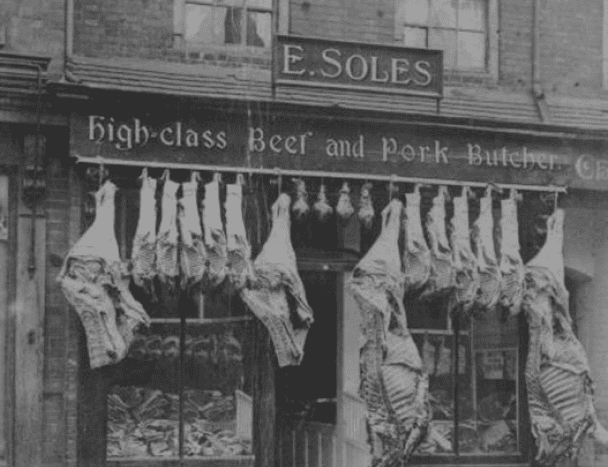

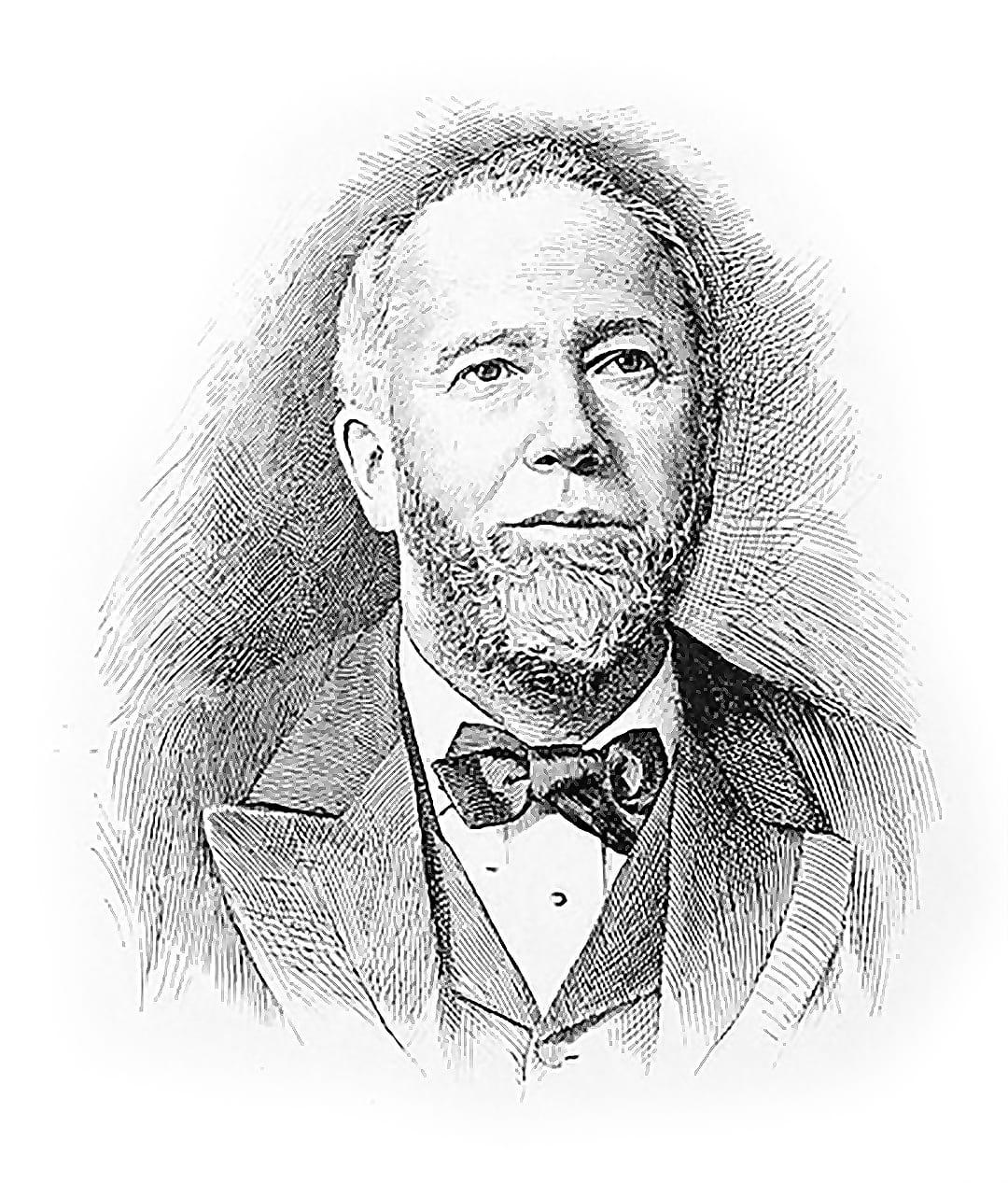

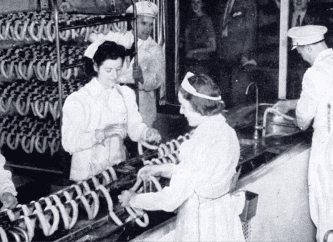

At age 16, Gustavus Swift founds his butcher shop business in Eastham, Massachusetts. With help from his family, Swift’s father advances him $20 for a heifer, with which he makes a $10 profit. Later, his uncle lends him $400 to start his business in earnest.

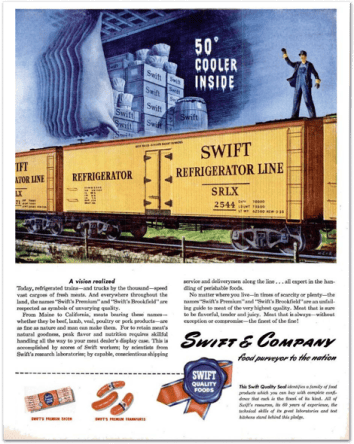

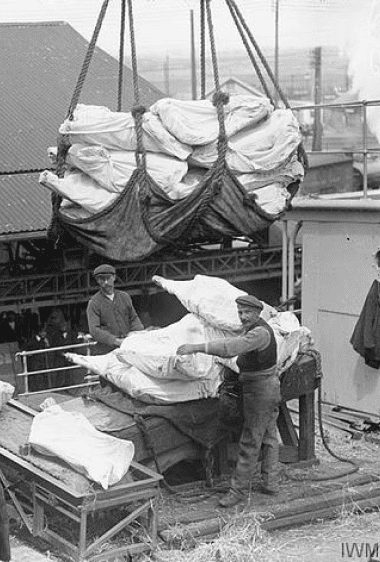

Swift then branches out to Brighton, Massachusetts, Albany, and Buffalo, New York. His next stop is the windy city of Chicago, where he establishes business there in 1875.

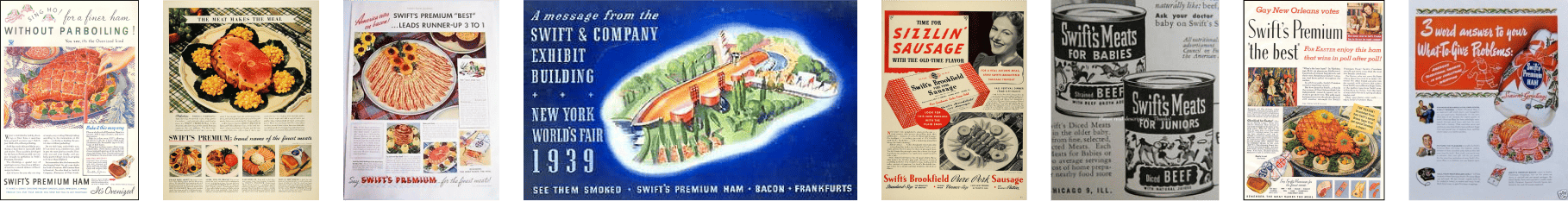

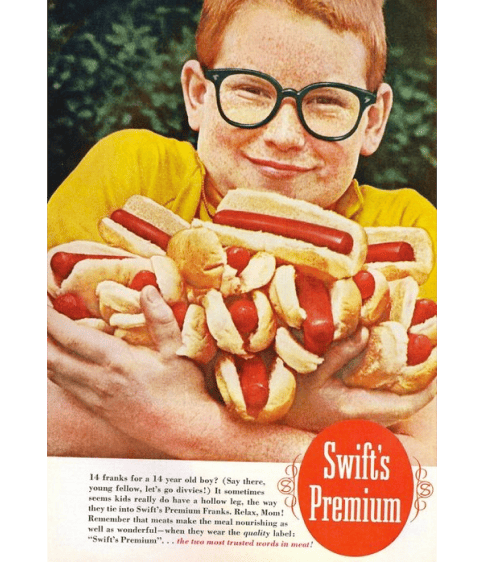

Take a journey with us, and discover the timeline of events that made Swift the brand it is today.

See how we’ve been inspiring the extraordinary since 1855.

Discover the timeline of events that made Swift the brand it is today.

Discover the timeline of events that made Swift the brand it is today.